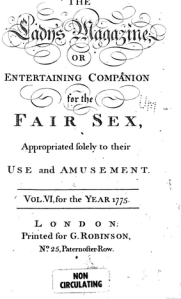

Over at the Lady’s Magazine project blog, Jennie Batchelor has posted about her research team’s deliberations about using the “p-word”–“plagiarism”–in relation to the Lady’s Magazine and its republication of writing taken from other printed sources.

As anyone who has perused the LM knows, every issue contains vast amounts of republished materials, sometimes with attribution, sometime with incorrect or misleading attributions, and often without any attribution at all. This kind of practice would certainly be considered a form of plagiarism today, but should we label it that way in retrospect? This turns out to be a surprisingly difficult question.

For one thing, the LM’s republishing of others’ content was never treated as a problem by the LM’s readers or even by its competitors; republication was a widely shared practice in both newspapers and magazines, and given tacit support by almost everyone involved. As Batchelor says,

The fact is that a significant number of contributions to the Lady’s Magazine were originally published elsewhere. The periodical did not conceal this fact from its readers. Often such extracts were published with their original author’s name and the full title of the work from which they were extracted or republished in full underneath the article headers. Indeed, the magazine was quite clear throughout its history that it would serve as a miscellany of works from ‘the whole circle of Polite Literature’ as appeared to the editor or editors to ‘merit their readers’ attention’, as well as providing a forum for the numerous original and amusing communications which we continually receive from our ingenious and liberal correspondents’ (‘Address to the Public’, LM XXIII [Jan 1792]: iv).

Yet the LM’s so-called “plagiarism” has become, for us, a much bigger problem, since we operate with very different assumptions about copyright, authorship, and commercial publishing. To complicate it further, today’s LM readers constitute a scholarly rather than commercial audience, and demand more definite information about the magazine and its sources than a casual reader might have desired during its heyday.

The question then becomes whether the scholarly critic or historian of the LM should retrospectively label the LM’s practice as plagiarism, and what is to be gained or lost by using such a term. For example, does giving up the term also entail abandoning attempts to identify the original authors, contexts, or venues of the writings that reappear in the LM? Conversely, could it be possible to continue using the term while dropping its moralistic overtones, which suggest some kind of “theft,” (of what? from whom?). Instead of fixating on these notions of immaterial theft, then, why not focus on the enormous network of contributors and sources that the LM helped to create?

Apart from the very real problems of authorial attribution that the LM research team is confronting in volume after volume, there is also the prospect of a fascinating conceptual payoff to this work, because both authorship and copyright were themselves undergoing radical redefinition during the period of the LM’s publication (e.g.,. the Ossian and Rowley controversies). Perhaps the editorial work will help us recognize this broader reconceptualization through the LM’s own evolving editorial practices.

Yet Batchelor admits that the already murky questions of copyright and plagiarism for literary genres become nearly opaque when we turn to 18c magazines’ editorial practice. So we are left with scant historical evidence about their ubiquitous borrowing.

My suspicion, though, is that the models for copyright and collective authorship in the magazine probably derived from newspapers rather than genres associated with single, named authors. For that reason, I believe the Lady’s Magazine project should drop the term “plagiarism” and use instead the term “republication,” which feels to me more descriptive of what the LM actually did and how it was perceived in its own historical moment.

Here are my reasons for dropping the term “plagiarism” from discussions of the LM:

The paradigm of intellectual property for the LM is not the single-author literary book, but the collectively generated newspaper. For the LM’s initial reading audience, the general practice for newspapers and periodicals had for a long time been a free and unrestricted republication, recirculation, or reworking of “found materials,” whether these were readers’ letters or printed matter. In an era without professional journalists, 18c newspapers could not have been filled week after week without massive amounts of reprinted or reader-supplied materials. Unlike the book-centered genre that most closely resembles the magazine, the anthology, the serial form of the magazine demanded large amounts of fresh content every month, and so the only practical solution to this limitless need was to capture as much content as possible from other printed sources and one’s readers.

In practice, this meant that any editorial staff (whose numbers rarely went beyond a single editor or a few reviewers) produced only a small percentage of a newspaper or magazine’s content, with the remaining items generated by the uncompensated labor of others, either as “extracts” of well-known writers, or as “the numerous amusing and original communications” written by the LM’s own “ingenious and liberal correspondents.”

It seems clear to me, then, that labeling these kinds of republications “plagiarized” would be anachronistic, given the ubiquity and acceptance of the practice, and the disinclination of contemporaries to label them this way.

“Piracy” might offer a less anachronistic term for republication than plagiarism, but even “piracy” was only rarely, and never successfully, applied to 18c periodicals’ republication practices in legal contexts. Since these uses of others’ material seems to have occurred more at the editorial than authorial level, “piracy”* might be a better, more historically apt term, though I don’t know of any cases where magazines’ republications were successfully equated with this era’s book piracy in this period’s law courts.

Will Slauter, for example, has argued that the 1710 Act of Anne “provided authors and booksellers with an exclusive right, during a limited period of time, to print, distribute, and sell their books. Yet the act made no mention of newspapers or other periodicals, whose status as literary property remained ambiguous well into the nineteenth century” (34). According to Slauter, 18c law courts tended to limit proprietors’ attempts to restrict the reworking or recirculation of their material. This was as true of extracts or adaptations as it was of periodical republications. The Act’s silence on this issue, however, did not prevent some publishers from registering their periodicals with the Stationer’s Company in the hopes of defending their property claims, though these forms of copyright were never formally challenged in court.

Thus, the proprietary claims of periodical publishers were treated with relative indifference by 18c courts and judges. This indifference towards the proprietary claims of periodical publishers, however, extended to the publishers themselves, according to Slauter:

such ownership claims [as patent holders’ printing rights for the king’s addresses] were rare with respect to most of the texts that filled eighteenth-century newspapers and magazines. No printer or editor would have dreamed of prohibiting the copying of paragraphs, because that would have made it much harder to fill his own columns. Politically speaking, it had also become more difficult to claim exclusive rights over news and political commentary. During the seventeenth century, censorship and literary property were linked, and news of state officially belonged to the monarch . . . . During the eighteenth century, by contrast, news became the property of the public, and in a journalistic culture that privileged the free circulation of anonymous paragraphs and pseudonymous essays, it because increasingly difficult to argue that accounts of current events could be owned” (55).

Thus, the courts, newspapers and writers arrived at a tacit consensus that permitted the widest possible reprinting and recirculation of paragraphs as “the basic nugget of news,” treating those paragraphs as a “textual unit” that

could be easily detached from one source and inserted into another. The type had to be set locally, which gave printer-editors the opportunity to modify texts for their local audience. In the process they often stripped paragraphs of references to the circuitous path that they had taken (54).

Since these paragraphs of “news” could not be considered anyone’s exclusive property, they were allowed to be reworked innumerable ways in order to encourage the broadest possible circulation of news and knowledge.

It seems to me, then, that the brief “textual units” of the LM, though formally and generically examples of short fiction, moral essays, biographies, etc., were nonetheless treated on the model of the newspapers’ “textual units,” as a kind of readily accessible, transformable information that could be extracted or reworked as needed.

The magazine itself constituted a genre with its own conventions governing use and re-use of others’ writing, consuming and re-presenting its constituent genres in its own characteristic ways. Batchelor generously acknowledges some of my work (currently under review) on the key generic features of 18c magazines, which she identifies as its “miscellany content,” and which I have described as its ability to “consume other genres.”

The magazine’s capacity to serve as a store-room or repository for varied things (harking back to its etymological origins as a warehouse or depot or armory) seems crucial to its appeal to 18c readers, who read magazines for their generic and authorial variety rather than intimate or extensive knowledge of a particular writer.Once again, it seems to me that this aspect of the magazine’s use–its ability to convey variety and multiplicity to its readers–seems the best way to understand the LM’s cultural functions at this time. And “plagiarism” tends to suggest very different kinds of use–essentially, the surreptitious theft of a named property–rather than the free exchanges suggested by “republication.”

DM

______________________________________________________

*Slauter describes one publisher who “defined plagiarism as ‘the surreptitious taking of passages out of any author’s compositions without naming him’ and piracy as ‘the invasion of another’s property by reprinting his copies to his detriment,'” the better to defend his own practice of printing extracts with the author and title fully identified (48).

UPDATE:

Since Dr. Konrad Claes has taken the time to follow up Batchelor’s initial post with a further response to my comments here, let me summarize where I think the discussion stands.

- I think we all agree that Slauter’s account of the Statute of Queen Anne leaves the precise legal status of non-book republication ambiguous.

- This does not mean, however, that authors and publishers did not sometimes try to protect their perceived property by rhetorically invoking the term, as in the case of Cave vs. Trapp, cited by Claes via Deazley. In these cases, Cave was forced to cease republishing extracts because he could not convince the judge he was not trying to reprint the entire work. Hence, magazines were always on safer ground publishing extracts rather than entire works. However, it seems to me that these extracts easily encompassed entire brief essays or stories, as portions of larger works.

- I believe that the distinction between plagiarism and piracy is maintained in the examples that Claes cites, when he shows that plagiarism usually describes an individual falsely submitting a work under his or her own name, whereas piracy describes a publisher like Cave simply reappropriating the work of another publisher. I look forward to Claes’s investigation of how both these terms were used throughout the long run of the LM

DM